I am in a book club that just throws a book at you at a club meeting, and it’s the book you’re meant to read for the next club. There is no preamble, no warning, no sneak peek. Sometimes this works for me, and sometimes it baffles me: should I read this book? I know nothing about it. This time, it really worked.

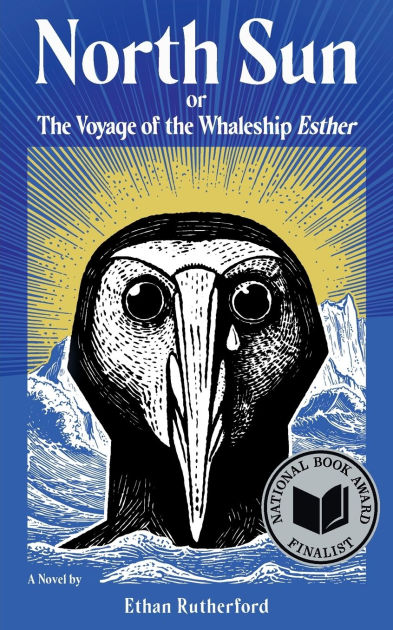

For one, when I went to work that week, I was keeping an eye on the book awards to make sure the bookshop was stocked with the books people would be seeking for the holidays. There was one big prize that was still not complete—a list of four finalists left. That was the National Book Award. And one of the finalists that I put on display at the front of the shop was North Sun: or The Voyage of the Whaleship Esther by Ethan Rutherford. The cover was striking, intriguing, And it didn’t look super long at 241 pages, which when you thumbed through was even less because of the layout of the text. More on that later. (It didn’t win. The True True Story of Raja the Gullible (and His Mother) won. I would like to read that one as well.)

I don’t think North Sun was expected to win any prizes, incidentally. It’s already in paperback. It has some typos. And it was backordered for a time after it had become a finalist. (That is speculation.)

It is a wonderful book, well-deserving of a prize.

Blub: It’s 1878 in Massachusetts, and the whaling industry is a dying one. Captain Arnold Lovejoy has just returned from an unsuccessful expedition, but he doesn’t feel content on land. Strangely, he has a letter to deliver to the world-famous, candle-making-empire Ashleys, and when he drops it off, they tag him for their next whaling/recovery expedition on one of the world’s best boats, the Esther. Before departure, Lovejoy meets the Ashleys’ daughter and gains two cabin boys, all of whom will have POVs. But things go sideways, as they will on a whaling ship that takes months to years to circle two continents and hit the Northern seas before the ice overtakes them. But this is really sideways. Can things this strange even be real?

Unfortunately, I have to give you some content warnings. These are no small potatoes. Obviously, there is killing of animals, often in super undignified ways. There is also child abuse and rape, though in much less graphic scenes (than the hunting and butchering of animals). I knew nothing of this when I started reading, and I wondered if I should continue once I got to the kids. Here is the deal: the book is historical fiction (or maybe historical magic realism); and it felt to me like we were seeing these cabin boys, remembering real kids who were shoved onto boats like this and most definitely exploited and abused often. Same with the whales: it’s history and it won’t do to forget. I not only made it through the book, I was entranced.

It is violent. It is bleak. But it’s also magical and fascinating, and man does Rutherford know how to write. In just a few sparse and unique words, I am there on the bow of the boat and the fish are swimming below me, a storm rising on the horizon, some idiot breathing down my neck. Whatever. All my senses were engaged, and I was spellbound.

Let me give you a peek at the writing:

“Steam rises from the Esther’s deck as she shakes herself from the weather to face the new morning. In the distance, white clouds convect into glorious shapes off the bow—branches of living coral, French meringues—to greet them. As the boys climb the mast, the damp rigging squeaks at their weight. From their perch, they can see the Esther has been washed. She looks new. / And to stern, they can see their old storm sweeping darkly behind them, prowling and punishing the sea” (Part 1, 74, p112).

Note: that is an entire “section” or “chapter” of this book. Which is what I was talking about with the layout on the page. Every 1-2 pages (for the most part) begins with a number and then one to several paragraphs before moving to the next page and beginning again. I’m not quite sure why we break it up so much. Breaks are always distracting to me, and I would have flown through this book much faster (though I already read it in two days) had the layout been more normal. But I also didn’t hate it. It felt different. And sometimes the way the sections connected—pioneering, brave, interesting.

We should all know by now that I love to be surprised as I read, too. And this book definitely did that. The surprises unfurl slowly, but they keep coming. And when you are done, the “reality” of the story is left up to you to determine or to figure out. It makes for good book club discussion. Which leads to the question of what this book is. Historical fiction? Magical realism? I kept seeing “climate fiction,” but I would not call it that. I landed on a psychedelic horror sea adventure. Also literary fiction.

What else did I have in my notes? There is definitely a tone of a fable here, as well as mythology with a pantheon like the Native American trickster gods, some fairy-tale even. It’s dreamlike, hallucinatory (which is accomplished at times directly, like during a fever or PTSD. Or an actual dream). There is some mystery. The writing is achingly beautiful but with such brutality and tragedy. There are layers to discuss, but do we need to? The reading was—for lack of a better word—enjoyable the first time through.

If you are the type, you will be looking things up during your reading. For what it’s worth, I could not figure out where the name Old Sorrel came from, except that Sorrel as a name would refer to red coloring and that made me wonder about the devil or an Egyptian or even Norse god (skin or hair). Shipworms are a real thing, a plague on wooden boats and a historical reality. Ambergris is a waxy substance from the digestive system of sperm whales that is highly prized in the perfume industry and was sometimes called “floating gold.” Several other things I couldn’t actually figure out by simple research.

I won’t give you my thoughts and theories about the ending or the overall mysteries of the book. I’ll let you discuss those with others once you’ve read the book. But I have my thoughts and theories.

And I’ve heard that if you like this book, you might want to take a trip to the House on the Rock outside Madison in Wisconsin. Look it up. I thought it might be interesting to go from here to A Marriage at Sea and then A Severe Mercy.

Ethan Rutherford lives in Connecticut and teaches creative writing at Trinity College. (He is from the opposite coast, Seattle, and went to school smack-dab in the middle in Minnesota.) He has two books of short stories and individual stories in various highbrow lit mags, which have garnered him many a fine award and recognition. But North Sun is his first novel, published in 2024 by a kinda smaller press. I’m not sure he expected all the praise he got for it, but any praise is well-deserved.

“…only to state the obvious—that a man, when stripped of his utility, understands with a great shame just how unnecessary to the Earth’s orbit he truly is” (p24).

“It is as easy to grin as it is to growl” (p71).

“But once they fall asleep, nothing can wake them. A blessing, one might say of such deep slumber. At the very least, it is necessary” (p98).

“The weather is a fact, a chapter in a story that must be read aloud to every sailor and won’t be rushed” (p110).

“One simply imagines better weather, elsewhere” (p111).

“But though the hunt itself is not kind, the speared fish are soon dead, and the utility of their bodies is a form of grace” (p121).

“’A ship is an interval,’ says Thule. ‘Think only on what’s ahead. See what’s in front of you. Make it so’” (p196).

“To be in this temperature is to be reminded that one is a body only, and the pain of understanding this stays with men forever” (p230).

“The wind whipped at his ankles, reared up, and hit him straight in the face. It was like conversing with someone who only talks and never listens” (p239).

“We do it for others, we do it for ourselves, perhaps. But we are purely instrumental; part of history pushing forward” (p253).

“Events unfold as they do regardless of how we feel about them” (p332).

“That they cannot speak, nor answer back; it’s in their design. Their suffering is theirs alone. It’s unheard. And to it I offer neither consolation nor advice” (p372).

Just a note…it is 241 chapters not 241 pages (as mentioned in the second paragraph). In my copy the novel itself is 380 pages (but reads much quicker because of the book’s layout).