I have been told since the drop of Olga Tokarczuk’s Drive Your Plow Over the Bones of the Dead that I needed to read it. So, when The Empusium showed up on bookshelves this year with its cool cover and then winkled its way onto one of my book clubs’ lists, I jumped at the chance. Unfortunately, it did not take long for my enthusiasm to wane, my attention to wander. But I could not put my finger on the disconnect. Only when I went to book club last night and talked it over with friends did I begin to understand. It wasn’t me. It was the writing style. It was the pacing, mostly, but also a lot of extra words. It was also the construction of Tokarczuk’s sentences.

Not that I hated it. There are great things to be said for this novel, but my overall experience was less than satisfactory.

Blurb: Mieczyslaw Wojnicz (Myech’ ih slav Voy’nitch) has just arrived at a health retreat for tuberculosis in Gorbersdorf, a forest town cradled in the mountains of the Austro-Hungarian empire. It is 1913, and Wojnicz is staying at the Guesthouse for Gentlemen while he waits for a spot to open at the famous Kurhaus. But amidst all the preening of the misogynist men around him, there’s something even weirder going on. Sounds in the attic. Cemeteries full of young men. Mushroom hunts and charcoal burners and spousal abuse, oh my! Not like Wojnicz doesn’t have his own past and his own secrets to contend with.

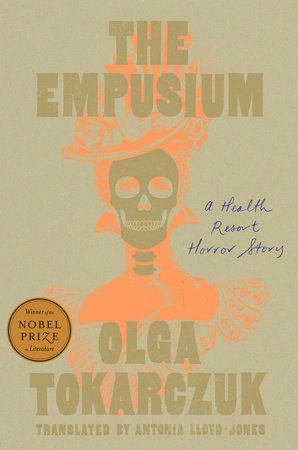

There is a subtitle: A Health Resort Horror Story. That’s kind of an interesting one. Instead of the more common “A Novel.” Tokarczuk’s subtitle is more something for the back of the book. And I don’t know that I would even label this “a health resort horror story.” It is horror, but more of light horror mixed with literary/historical thriller. A translated work from a Polish writer who won the Booker and a Pulitzer a handful of years ago.

I already bought Drive Your Plow Over the Bones of the Dead, thinking I will probably like it more than this one. I am getting mixed signals, though. My co-workers who have read both, say Drive Your Plow is better and I should read it. The one reader at book club who had read Drive said that my struggles with Tokarczuk’s writing style would still be a problem in Drive. I guess we’ll see. I wonder how much of it is translation issues. (It can’t all be translation issues, like story pacing and the lack of sneaking pertinent info in early.)

About the structure of this book. I like innovative structure when it works, and actually the innovative structure here does work, despite the other issues. The narrator’s voice is third person limited, past tense, in Wojnicz’s head. Chronological over a few months with flashbacks to his past when he thinks about the memories. Until it isn’t. There is also a mysterious first-person voice that cuts in, in present tense. And we aren’t allowed to know who or what this voice is (not until the end, anyhow. Someone accidentally told me but thank goodness they were wrong). Just thought you should know. (I love to know a book’s basic structure before I dive in.)

Another thing I would have liked to know before I began: the book is based on The Magic Mountain by Thomas Mann. There was only one person at club who had read this book before, and she said that though it is very long, she really liked it. She liked it much better than The Empusium. I would have liked the opportunity to read it first, though I have to admit I probably would not have been able to get to it, this summer. When I read David Copperfield before Demon Copperhead and The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn before James, I found my experience to be much edified. And clarified. Ah, well.

And yet another thing I would have liked to know before I began: the crazy, anti-women opinions of the men in this book are actually direct quotations from ancient to Edwardian scholars, philosophers, politicians, writers, theologians, psychologists… I was kind of exasperated reading all of them, but I trusted there was a point to the direct misogyny. Had I known she was playing with actual, historical words, I would have been more interested and less distracted (though no less disgusted) by the “gentlemen’s” tirades. And still trusted that it was going to make sense to the story eventually. You can find more detailed information at the end of the book.

Speaking of eventualities, as one clubber said last night, “It was about the destination, not the journey.” Another person called the ending “fire,” you know, like the kids say. After all my slogging through and being distracted and wondering why it was taking me so long to read, the ending was where almost all the power of the book was located. (Funnily enough, it was just oblique enough that there were some disagreements about what actually happened and what secrets were revealed. I feel confident I know what happened, but…)

There’s a lot going on in this book that I can’t discuss in a review. Discussion even of many of the themes and the little things tucked away (even in the title) would be plunging into spoilers. I can say that innocence and loss of innocence is one theme. And that shwarmerei is not a real beverage, but something Tokarczuk made up for the book. Those are not spoilers.

Had Tokarczuk cut like 100 or 150 pages, I think I would have enjoyed it more. However, there really is something about her pacing, her cadence, that keeps me from fully engaging, even when her language is beautiful and the setting lush and creepy. I don’t know how to explain it except for what another book club member said, “My brain wiped over the words.” Yes. My brain wiped over the words and I returned again and again to re-read whole paragraphs of which I had absorbed nothing. Perhaps Tokarczuk and I are just not a great pair. Perhaps my attention is too 2025. (For what it’s worth, I just read Hamlet and 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea and am reading Persuasion and doing just fine.)

(She also did one of my pet peeves, which is introduced us to a number of the main characters at the same time, which resulted in the critique that readers couldn’t keep them straight and that they never distinguished themselves.)

Would I recommend The Empusium? That’s a tough one. There is much to be excited about in this book, but quite frankly I was bored about 85% of the time. Yikes. That’s not great odds. If you like creepy, atmospheric, feminist, literary stuff with lots of food and scenery and the slowest of builds (and also sparse, silly, unneeded illustrations), then this might be your favorite book this year. I’m not upset I’ve read it, but it was unpleasant for me much of the time while I was doing so.

“He thinks he is about to cough up his soul” (p5).

“Life in a crowd is worse than prison” (p13).

“…let us tell ourselves the truth directly, however dreadful it may be” (p40).

“Do you know what is the most common mistake people make when they’re in danger? Each one thinks their life is unique, and that death doesn’t affect them. No one believes in their own death” (p49).

“…a single nation-state has no raison d’etre, the essence of their existence is confrontation and being different. Sooner or later, it will lead to war” (p96).

“The quotation is a legitimate literary genre” (p96).

“Wojnicz was too young to take a real interest in politics. What was happening inside him seemed far more intense than the world’s most dramatic political events” (p110).

“So every day after lunch, just as the body was digesting and a gentle afternoon somnolence was suffusing it…” (p142-143).

“Making moves according to the rules and aiming to defeat your opponent seemed to him just one of the possible ways to use the pawns. He preferred to daydream, and to see the chessboard as a space where the fate of the unfortunate pawns and other pieces were played out…” (p 143).

“Shouldn’t women dress up in some sort of uniforms, too, and wear medals according to how many children they’ve had, how many dinners they’ve cooked, or how many patients they’ve nursed? That would be both beautiful and fair” (p145).

“…we tend to like things we have grown used to” (p183).

“My point is that we may be similarly disabled inhabitants of a world that consists of three dimensions, and we shall never know what a four-dimensional would is like. Do you see? We have no tools or senses to introduce us to a world with an extra dimension, let alone a fifth, and a seventh, and a twenty-sixth. Our minds cannot conceive of it” (p191).

“Our world may be nothing but a shadow cast by four-dimensional phenomena onto the screens of our senses” (p192).

“The gentlemen began to lecture each other, each presenting his position as though pulling the topic over to his side, like a too-small quilt” (p193).

“We are shaped not by what is strong in us but by the anomaly, by whatever is weak and not accepted” (p272).