I was excited to read Ursula K. Le Guin’s The Lathe of Heaven because it is short, a classic, and I hadn’t gotten around to Earthsea just yet. I think I was expecting more fantasy than science fiction, but I have loved classic sci-fi before (like Ray Bradbury). For the first while I was just okay with it, but it kept me reading. And by the time I finished, and even moreso as I discussed it with others, I realized that I really liked the book. It’s a great book. Almost everyone at book club agreed. For some people, it’s even one of those books they come back to again and again, which I totally understand.

George Orr has been trying to stay awake, indefinitely, or at least drug himself into dreamless nights. But drugs are regulated in an overpopulated, near-scorched-Earth future, and George is sent to a psychiatrist, Dr. Haber, to keep him out of prison for drug use. But how could Haber help him if he’s sure not to even believe him?: George’s been avoiding sleep because sometimes his dreams change reality. It doesn’t take long before Haber catches on and George is looking for help, any kind of help, to get him out from under Haber’s “care,” the world continuing to shift as the dreams stretch, under Haber’s control, for a utopia that is completely out of reach.

I read this book for my speculative fiction book club. I was expecting the high fantasy of Le Guin’s popular Earthsea Cycle, but it turns out she is also famous for sci fi and for a number of other books and worlds, like The Left Hand of Darkness and The Dispossessed, both of which are on my TBR even though I wouldn’t have known them if they bit me in the butt.

By the end of the book, I had some real Wrinkle in Time vibes, but I actually think The Lathe of Heaven delivers in ways that Wrinkle did not. Not that they’re totally similar. (I mean, Lathe is for an adult audience while Wrinkle is for kids.) Lathe starts slow, but at some point you realize that the book is laced with a series of surprises and twists delivered (mostly) with quiet subtlety, moments in which suddenly there is ice in your stomach or you’re gritting your teeth. Part of me could not believe this was published in 1971 except that it does have that classic sci-fi feel. Others said they felt some of it was out of date, but I really didn’t think so at all—the amount of insight that Le Guin had regarding the problems and culture of today coupled with the reality of the world she paints being totally believable as just a decade or so in our future… I was stunned by how much Lathe still resonates for us in 2024.

Like I said, I enjoyed the twists and turns. The reading experience was great. The book is short, almost a novella, with an impressive writing style. It doesn’t actually have time travel in it, but there are elements to the plot that would make it appealing to readers who enjoy time travel literature. And in the end, well, I liked the way it ended, like what it had to say as a book in the final chapters. (I agree with some people that the climax was a bit psychedelic or disjointed or something, confusing maybe, and that George didn’t quite earn his ending, but overall I was happy with it.)

Central to Lathe is Le Guin’s Taoism. Yes, Taoism. It influenced many of her works, but here we know it is overt because the title comes from a translation of the Tao Te Ching. There is a lengthy but interesting article about her Taoism and its effects on her works at Inglenook Lit, which I encourage you to read it this is interesting to you. Someone in book club even brought up The Tao of Pooh, a Western simplification of Taoism taught through the character of Winnie-the-Pooh (by Benjamin Hoff) that I read—in my free time—in college. So while someone at book club complained that George “couldn’t punch his way out of a paper bag,” this is a pretty Western way of seeing an Eastern-inspired character. Personally, I liked George. I know laid back people like him and there is plenty to respect about this approach to life (though George floundered because he had to grow or where would the story be and he didn’t have it all together).

It would make a great re-read, what with all the themes of Taoism versus Utilitarianism, East versus West, dominance versus submissiveness, responsibility, heroism, dreams, power, even race and environmentalism. Even the good guys in Lathe have kernels of corruption. The Second Law of Thermodynamics is in play, here, as life marches ever toward chaos even as hopeful dictators strive toward a utopia that can never be. (You could also read this as yin/yang and how balance prevails.) There is no totally winning scenario in this “Monkey’s Paw” of a story. As another person at book club said, “This is an ideas book, first.” Like a lot of speculative fiction, especially sci-fi, the characters and setting are tools being used for a greater message. It’s not a character study. It’s a warning.

And though George gives himself away with his last name, Orr (= either/or), I didn’t think George was just faffing about. (Haber also refers to hubris and George Orr’s name could also be a reference to George Orwell.) There was some action in George, he was just in an impossible position on an impossible timeline. He didn’t have time to figure it out, especially when others were willing to be so violent with their good intentions. Passion is part of humanity, it contributes to our quality of life, even, but what does it lead to? Humans are not very good at turning good intentions into real health and solutions, it turns out.

There are other things, too. Some call it a comedy. If so, it’s very dry. And the sub-theme regarding race is done so well. Le Guin was certainly thinking ahead of her time, lamenting the idea of a gray race with the line, “You should be brown.” Identity is important. Life would be missing something essential if we were clones, if we were homogenous.

So, yeah, I liked this book, maybe even loved it. I handed it off to my husband because I knew that he, too, would really enjoy it. (He is; he’s almost done.) It’s a classic of science fiction, one that I think can be read fairly easily even still. There’s a lot to talk about, but it can also be read simply for enjoyment, the enjoyment of good storytelling and good writing style.

Ursula K. Le Guin was born in the 1920s and started publishing sci fi and fantasy in the 60s. By the time she died at almost 90 years old, she had published 23 novels, 12 short story collections, 11 poetry collections, 13 children’s books, five essay collections, and four translations (including the Tao Te Ching). She received six Nebula Awards and seven Hugos, a PEN, National Book Foundation Medal for Contribution to American Letters, and many others.

Some of her award-winning books include:

- The Books of Earthsea, beginning with The Wizard of Earthsea

- The Novels of the Ecumen beginning with Rocannon’s World and including both The Left Hand of Darkness and The Dispossessed

- The Lathe of Heaven

- The Winds Twelve Quarters (short story collection)

- Dancing at the Edge of the World (essay collection)

- A Fisherman of the Inland Sea (short stories)

- Always Coming Home

If you read the Books of Earthsea, the Novels of Ecumen, and The Lathe of Heaven, you have probably covered her best work.

Her website is still in operation and you can find lots of information HERE.

“…for in the deep sea there is no compass but nearer and farther, higher and lower…” (p1).

“…the most vulnerable and insubstantial creature [jellyfish], it has for its defense the violence and power of the whole ocean, to which it has entrusted its being, its going, and its will” (p1).

“So often he knew what his patients were going to say, and could say it for them better than they could say it for themselves. But it was their taking the step that counted” (p10).

“The insistent permissiveness of the late twentieth century had produced fully as much sex-guilt and sex-fear in its heirs as had the insistent repressiveness of the late nineteenth century” (p12).

“Orr had a tendency to assume that people knew what they were doing, perhaps because he generally assumed that he did not” (p29).

“He thought, I am living in a nightmare, from which from time to time I wake in sleep” (p38).

“What sane person could live in this world and not be crazy?” (p44).

“”It occurs in other brains, undoubtedly. Nothing’s new” (p62).

“…he had accepted it totally, just as they did, as the only reality. He had suppressed his memory of the fact that, until last Friday, this had not been the way it was” (p63).

“My God, he thought, what has Orr done? / Six billion people. Where are they?” (p65).

“The danger was past. She was rejecting the incredible experience. She was asking herself now, what’s wrong with me?” (p65).

“Of course, Haber thought, a man who saw a miracle would reject his eye’s witness, if those with him was nothing” (p65).

“That’s what strikes humans as uncanny about sleep. Its utter privacy. The sleeper turns his back on everyone” (pp66-67).

“But he’s not a mad scientist, Orr thought dully, he’s a pretty sane one, or he was. It’s the chance of power that my dreams give him that twists him around” (p75).

“Haber was, after all, a benevolent man, And besides, he didn’t want to kill the goose that laid the golden eggs” (p77).

“Nothing will keep a man from dreaming, he had said, but death” (p79).

“You speak as if that were some kind of general moral imperative” (p82).

“What we do is like wind blowing on the grass” (p82).

“This was the way he had to go; he had no choice. Be had never had any choice. He was only a dreamer” (p83).

“’Out of the frying pan into the fire,’ Orr said. ‘Don’t you see, Dr. Haber, that’s all you’ll ever get from me?’” (p86).

“’What kind of monsters have you dredged up out of my unconscious mind, in the name of peace? I don’t even know!’” (p87).

“For all he knew, Haber was incapable of sincerity because he was lying to himself” (p87).

“Look, if you ask me to dream again, what will you get? Maybe a totally insane world, the product of an insane mind. Monsters, ghosts, witches, dragons, transformations—all the stuff we carry around with us, all the horrors of childhood, the night fears, the nightmares. How can you keep all that from getting loose? I can’t stop it. I’m not in control!” (p88).

“Liar builds pitfall, falls in it” (p91).

“…a man whose personal dignity went so deep as to be nearly invisible …. It was more than dignity. Integrity? Wholeness?” (p96).

“Are there really people without resentment, without hate? she wondered. People who never go cross-grained to the universe? Who recognize evil, and resist evil, and yet are utterly unaffected by it?” (p100).

“This isn’t real. This world isn’t even probable. It was the truth. It was what happened. We’re all dead, and we spoiled the world before we died. There is nothing left. Nothing but dreams …. ‘So what? Maybe that’s all that’s ever been!’” (p107).

“Only those who have denied their being yearn to play at [being God]” (p109).

“He needed somebody, anybody, to talk to, he had to tell them what he felt so that he knew if he felt anything” (p115).

“Great self-destruction follows upon unfounded fear” (p121).

“If Haber had suggested that he dream up a nobler race of men, he had failed to do so” (p127).

“But now, never to have known a woman with brown skin, brown skin and wiry black hair cut very short so that the elegant line of the skull showed like the curve of a bronze vase—no, that was wrong” (p130).

“This building could stand up to anything left on Earth, except perhaps Mount Hood. Or a bad dream” (p136).

“’Life—evolution—the whole universe of space-time, matter/energy—existence itself—is essentially change.’ / ‘That is one aspect of it,’ Orr said. ‘The other is stillness’” (p139).

“Life itself is a huge gamble against the odds, against all odds! You can’t try to live safely, there’s no such thing as safety” (p139).

“I know you’d give her the serum, because you have it, and feel sorry for her. But you don’t know whether what you’re doing is good or evil or both…” (p140).

“Love doesn’t just sit there, like a stone, it has to be made, like bread; remade all the time, made new” (p159).

“He seemed not to know the uses of silence” (p164).

“There is time. There are returns. To go is to return” (p184).

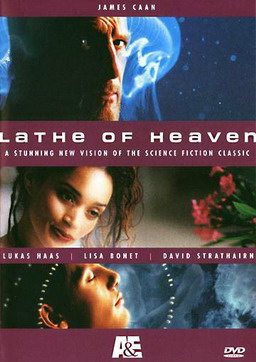

The Lathe of Heaven has been made into a movie at least twice. The 1980 version is, I’m sure, largely out of date in some ways, but it has high ratings. Maybe we should approach it as a movie of ideas? The 2002 made-for-TV movie didn’t get as much respect, but it does star Lisa Bonet, aka. Denise from The Cosby Show and A Different World. (I was a big fan of Denise.) Maybe my husband and I will try to find copies of at least the 1980 version and watch it in the next couple weeks.