There is a list of reasons why readers think Stay True by Hua Hsu should not have won the Pulitzer (memoir). I think the most compelling (if also backwards) of those reasons is that the award builds expectations that this book cannot live up to. If it didn’t have that Pulitzer hanging over its head, I actually think most readers would like it more than they do. Expectations and all that. Maybe this review will save you from that, by way of pointing out all its faults and telling you that even a crowd of fairly pretentious people at book club were mystified by the Pulitzer here. Then again, most of those same people at least liked the book. I came across as hating the book, but I was really posing a series of questions I wondered about as I read. That constant questioning was made possible because I was never immersed in this book, never taken into a story or drawn into a character, even the main one. But man could I relate. And I didn’t hate it. Overall, I liked it. But there is a line.

Hua Hsu was a Taiwanese-Californian teenager in the 90s. He headed to college at Berkeley in 1995 and made unlikely friends with Ken, a much more mainstream and friendly Asian-American than Hua. While Hua was obsessed with alternative music, non-fashion and philosophy as well as his zine, Ken was a ray of carefree fun. When a tragedy interrupts Hua’s coming-of-age, he begins to document his college life and his friends down to the minutiae, looking for answers in the senseless pain that has found him out.

NOTE: I believe it best if you do not read the description for this book on the back cover or online. It gives away the only real event/climax of the story (or is it the inciting incident?). Major spoiler. If you already have, well then that’s on the publicists or publishers or whomever. I can appreciate if Hsu doesn’t want the story to hang completely on this moment… that’s actually kind of a point he makes by the end of the book. In that case, he doesn’t want you anticipating or dwelling on a scene which, quite frankly, he makes so little of (like in time talking about the actual event and in the anti-drama of the scene itself). That moment in time is not the essence of who Hua or Ken are. (Think of people advocating for killers’ names to be kept out of the media. It’s kind of like that. Their fame is detrimental to the overall process for everyone. In this case, dwelling on that one scene would give it too much weight.) I could be giving too much credit to Hsu for this decision, but I find it a distinct possibility. At any rate, if you want to feel a little traditional tension during this read, if you want to wonder for at least half of the book what will happen, then don’t read descriptions.

Like I half-said, I read this book for a book club. It’s like the cool, hipster book club I go to (cool for older people, okay?), and this is the second book of what promises to be many nose-lifting reads. I finished it like a week before the book club night and was convinced my husband would like to read it, too. I invited him to the club and passed him the book. It is important that I give him some voice here: he is much happier with this book than I am. Basically, he likes it just the way it is. Perhaps without the Pulitzer.

Hua’s voice got to me, right under my skin. In two ways. At first, I was like, Oh my goodness, I recognize this voice! I was this person in high school and into college! Sure, we have some major differences, but we are two years apart in school, both identified with the counter-cultures of the nineties, studied philosophy, and, as a bonus, I was visiting relatives in Berkeley while he went there. I recognized most of the references, was taken back to a time and a place; I was there at the computer console as this infantile internet thing awed us; I was there in the head shops smelling incense and reading the beat-up fliers; I was there surrounded by college philosophy texts. But as I kept reading the book, his voice as a narrator (as opposed to character) is, um, similar. Page after page after page I waited, longed, for some perspective, some second voice to look back on Hsu’s formative years and have some different approach, have something to say about it. And while I will own up to being as insufferable (at least in areas) as the young Hau was, the reader never leaves this insufferableness. Can it be that Hsu hasn’t changed? That he never matured? Unknown. But it certainly sounds and feels like it. At least the book is short.

While I wonder if this teenage tone is intentional, I also wondered if Hsu put the climax in the middle and downplayed it intentionally (as I already mentioned). And I wondered if… and somewhere in there, a member of the club said, “I think you guys are giving this author too much credit.” I laughed, we all laughed. He might be right. He’s probably right. Has Hsu earned my trust with, say, another book? No. Was the Pulitzer making me read too much between the lines? Possibly. Probably. Almost for sure. Or maybe it was the self-consciousness and hoitiness of the voice, itself. Surely I was the one not catching on. I mean, I don’t even have a grungy ‘zine or polyester pants (anymore). I just don’t get him.

Put another way, while Hsu’s making some fun of the teenager he used to be, I still felt contempt coming from the narrator to his teen self, which is ironic because he is making fun of his judgmental, clueless personality. He doesn’t seem to have learned, as his father would say, that these years are necessarily transitional and rocky. Having been a teen much like Hsu, I was floundering, looking for some compassion to seep into his voice, some levity and perspective on himself at an earlier age or at least of the times in general (and all the teens around him and through time). His voice is so caustic. We get it: he’s super smart and he thinks really deeply about everything; but Hua and Hsu (as both character and writer) are tellers. We have to take him at his word for everything—there is no showing, no natural development of people or themes or plots. I am suspicious of this. When other readers express emotional response to this book, I suspect that they take people at their word instead of having to experience a thing.

And as I dug in, I found myself bored as well as offended. Where are the stories? Where are the shades of characters? It’s a straight-up info dump about his parents, his father, their immigration and reverse-immigration, his high school years, followed by college. I’m actually yawning, feeling like I have been assigned an article for school. And it doesn’t change. The pivotal moment comes in the middle of the book and is glazed over. The latter half of the book actually slows down, leaving us nostalgic for the father character we met in the first pages. Then we end with a therapist, which I have argued before is not a satisfactory way to conclude a book, even though it is a great thing to do in life. Good gracious. I know it’s a memoir, but other memoirists have managed a plot arc, nuanced characters, interesting scenes, even descriptions that put is in a time and place. Or at least a unifying theme. I wonder if I am bored and if I don’t know what this book is about because I have already been there before. I uncover themes (immigration, existential crises, friendship…) that tantalize me only to disappear a few pages later, the chronology moved on to whatever next, banal thing Hua was going to hyperfocus on and whine about.

I exaggerate. There are some things I enjoyed about this book as I went, mainly the nostalgia, the honesty of the teenage experience, and Hua’s dad. (Hua’s dad gets five stars.) There were many things I wanted to like about it. But in the end I was more disappointed than entertained. Yet, I respect that the girl next to me in that giant book circle absolutely loved the book—as an Asian-American, no less. I also appreciate that my husband really liked it, just the way it is; I suspected he would, actually. But if you are a little lost for positive words upon closing this book, I extend a hand to you, as well. It’s not you, it’s Hsu. And the Pulitzer committee.

For kicks, among the bad reviews that called the book “flat” and “unending with details,” you can read a short, funny one-star review by Vida on Goodreads.

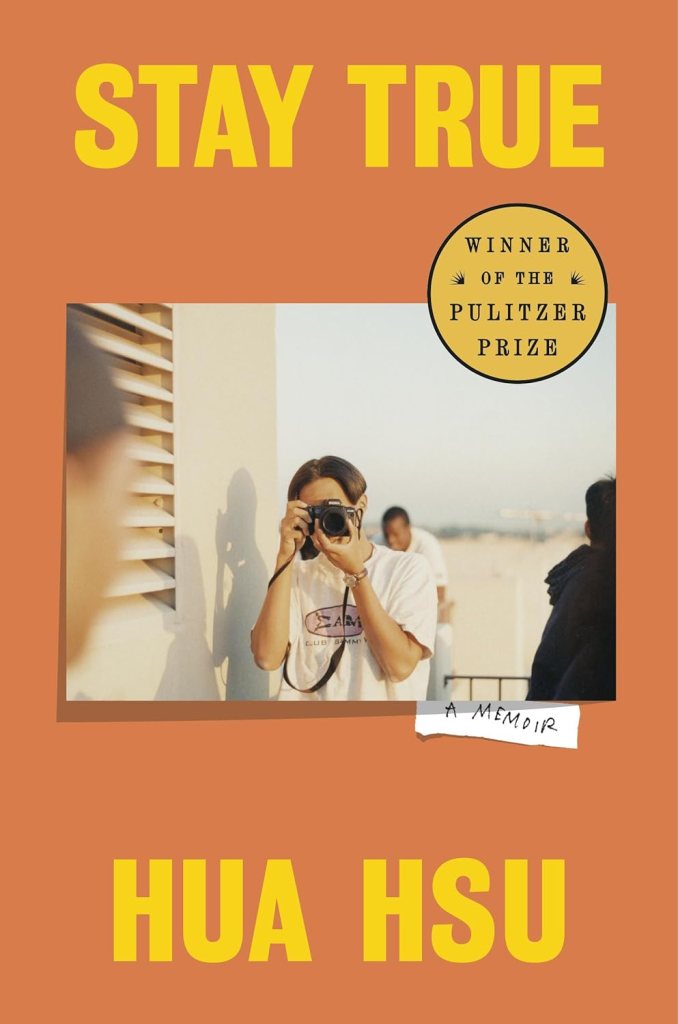

I also forgot to mention how much I didn’t like the photos in the book. They were sparse and artistically blurry and all that. Not my cuppa for a biography. I want ample and clear photos of who and where and what is being talked about, not the worst photos from some guy’s college album. And the barely-different font for the quotes was a strange (and bad) choice. I doubt everyone even noticed it.

The thing to know about Hsu is that he is a staff writer for The New Yorker. He also teaches literature at Bard College, lives in New York City, and went to Harvard as well as Berkeley. He’s placed short stories at The Atlantic, Slate, and The Wire and even been nominated for a James Beard Award for food writing. We probably shouldn’t mention that one of his areas of expertise is arts criticism.

HERE is a page at The New Yorker where you can read his latest articles.

“I’d heard these songs hundreds of times before. But to listen to them with other people: it was what I’d been waiting for” (p4).

“Assimilation was not the problem to be solved, but the problem itself” (p25).

“’…you have to find meaning, but by the same time, you have to accept the reality. How to handle the contradiction is a challenge to everyone of us. What do you think?’” (p32, Hua’s dad).

“There are many currencies to friendship” (p44).

“We learn as children that friendship is casual and transient. As a structure, it’s rife with imbalance, invisible tiers, pettiness, and insecurity, stretches when we simply disappear” (p45).

“We weren’t in search of answers. These weren’t debates to be won …. We were in search of patterns that would bring the world into focus” (p49).

“Ken knew how to use people—not in an exploitative way, but he understood what key you sang in. He could inspire you to do strange things, and he knew when to defer. Derrida remarked that friendship’s driver isn’t the pursuit of someone who is just like you. A friend, he wrote, would ‘choose knowing rather than being known’” (p56-57).

“We seek recognition, even if what you want to hear from a close friend is that you’re a one-of-a-kind weirdo that they’ll never truly understand” (p81).

“A spore takes flight by wind, and the whole system survives. The assassin blinks, and the bullet merely grazes the head of state. The planet’s axis shifts imperceptibly, and Earth is ruled by some other species. It’s not even called Earth; there is no language at all. The letter is lost in the mail, the opportunity gone forever. / All my classes in college essentially taught the same lesson: another world was once possible” (p103).

“’It is useless to go looking for goodness and happiness far away,’ [Mauss] concludes. They’re closer than you think” (p105).

“…I found it upsetting you could spend so much time with someone and not realize how small their head was” (p123).

“What was that thing we had learned in our rhetoric class, about Derrida’s ‘deferral of meaning’ and how words are merely signs that can never fully summon what they mean? Yet words are all we have, simultaneously bringing us closer, casting us farther away” (p125).

“Sometimes, things are fucked up. You take refuge somewhere and realize it’s not the dream after all. Cops harass you for no reason; your weary parents’ moods seem governed by forces you can’t yet name. Your otherwise mild-mannered, twenty-one-year-old mentor comes running at you, absolutely hell-bent on glory” (p137).

“Our nation was haunted by ghosts” (p148).

“I think the most depressing aspect of keeping a journal is thinking, or knowing, that one day I’ll be sitting somewhere reading this. Trying to relive some moments, but struck not be recaptured emotions, rather being struck by how damn deep I tried to sound at some point in the past” (p150).

“I humored the possibility that providence was still real, only that it was fickle—that maybe it was some other ghost’s chance to taste victory” (p152).

“I wondered in my journal if death was worse than the knowledge that the world continues outside” (p163).

“To understand the past, we must reckon with the historian’s own entanglements, the way past, present, and future remain forever ‘linked together in the endless chain of history’ …. The only truth is that it’s fucked up the way it is sometimes” (p175).

“All of these miniscule, knowable facts … they couldn’t possible explain why they had done it. No context made their actions ‘inevitable’ or ‘unavoidable’” (p180).

Pingback: What to Read in February | the starving artist

Very great points. I do agree that it is a great book but probably didn’t deserve a Pulitzer.